LGBTQ+ History: A Brief History of Gayborhoods in the U.S.

By Lilly Milman

Jun 21, 2023

San Francisco’s Castro District, Philadelphia’s Gayborhood, and Chicago’s Northalsted district (formerly known as Boystown) were once all famous centers of life in the United States — and each of these cities is adorned with nods to this history, like rainbow crosswalks, flags, and signs.

But these cities weren’t always so proud of the history being made there. Called “gayborhoods” (a portmanteau used to describe neighborhoods that are hubs for LGBT+ communities), these areas have evolved greatly over the 20th and 21st centuries — from neighborhoods where LGBT+ individuals were forced to self-segregate to proud parts of a city’s history and culture.

We dive into the history of gayborhoods in the U.S. along with activist and community organizer, Harvard professor, historian, and author of A Queer History of the United States, Michael Bronski.

Finding the First Safe Spaces

So, when, how, and why did gayborhoods form?

Unsurprisingly, where gayborhoods formed often came down to real estate trends. For example, when Boston’s South End was attracting a lot of LGBT+ individuals in the 1970s, it was because it was cheap to rent or even buy real estate in the neighborhood. Typically, Brosnki explains, gayborhoods formed in old immigrant neighborhoods. He named Greenwich Village in New York City and North Beach in San Francisco as a few other examples.

Initially, these weren’t the rainbow-covered neighborhoods we know today. Bronski and other historians call the first iterations of these gay communities “gay ghettos,” and note that many same-sex couples felt forced to self-segregate in them to avoid being persecuted by “polite society” at the time.

“If two men kissed on the street, they could be arrested for being disorderly. The word disorderly literally comes from the legal usage — which is out of the accepted order of things,” Bronski says. “Gay ghettos arose from the very notion that people found a place to go where they were safe.”

The desire to feel safe bled into the culture of the LGBTQ+ communities that formed. According to Bronski, two of the most popular songs in gay bars in the 1960s were “There’s a Safe Place for You” from West Side Story and “Somewhere Over the Rainbow.”

Putting Down Roots

The seeds for many gayborhoods were planted in coastal, port cities, where boats would land immediately following the conclusion of World War II. Many of the veterans, who had been made to leave home at the first sign of adulthood, didn’t want to return to their small rural or suburban towns where they would be forced back into the status quo. So, they landed in places like Baltimore, New York, Boston, San Francisco, and Los Angeles — and stayed. This trend created a sort-of whisper network: “Greenwich Village has a long history of being artistic and being bohemian. Gay people began to move there and it got a reputation — then more gay people moved there,” Bronski says.

Over time, businesses run by LGBT+ veterans began to pop up and communities started to flourish. The GI Bill, which funded education and offered government backing on loans for veterans, contributed to a number of LGBT-run business opening.

“You couldn't work in a major company without being closeted,” Bronski says. “When you think of Greenwich Village in the ‘50s, you think of … people running alternatives shops, all of which is funded by the government if they were veterans. It was easier for you to actually run an antique store in the Village than have to be closeted and work for [a major corporation].”

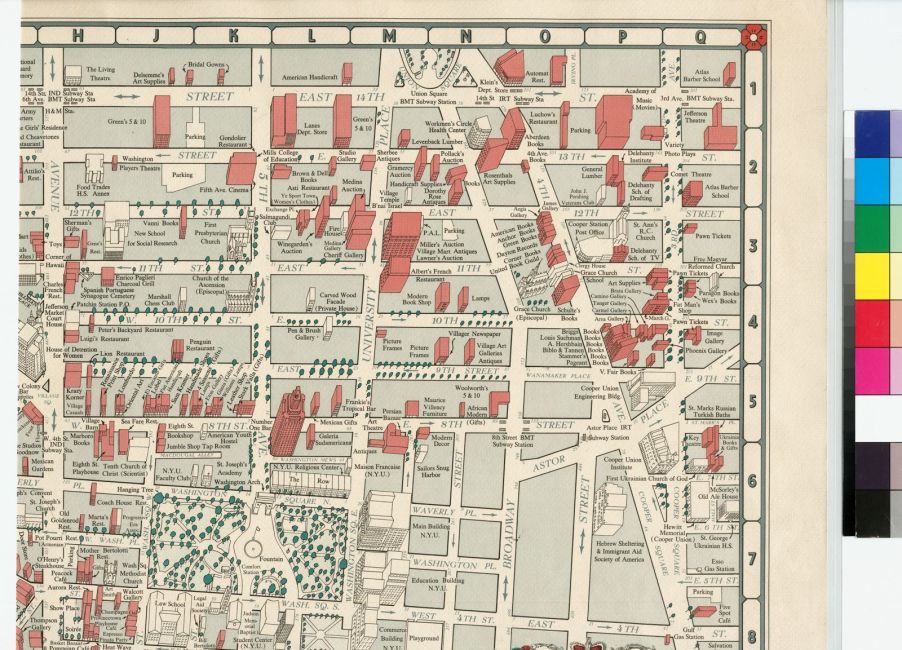

A map of Greenwich Village issued in 1960.

A map of Greenwich Village issued in 1960.

Creating Community

Not only did these coastal city neighborhoods present economic opportunities, but they also lent themselves to creating community. Higher-density development meant that there were a lot of smaller, cheap apartments — but there were also plenty of outdoor and third spaces where one could meet other gay people, like cafes, bars, and parks.

“That led to a community building atmosphere out on the street,” Bronski says, which sparked community organization and events.

Bronski himself was present in these spaces at the time — becoming involved with the gay rights movements in New York and later in Boston, where he worked at multiple LGBT+ publications for over 20 years.

Politically, gayborhoods were also crucial, as the clustering of LGBT+ people helped create “voting blocs” that helped create policy change, which led to greater human rights protections for people of all sexual orientations and gender identities, write Alex Bitterman and Daniel Baldwin Hess in their book The Life and Afterlife of Gay Neighborhoods: Renaissance and Resurgance. Those who lived in gayborhoods were pioneers in the fight for civil rights.

Beacons of Culture

Colloquially, many gayborhoods also have the reputations of being centers of counterculture, activism, and art. Bronski argues that “vibrant American culture comes from the margins.”

“The notion that gay men are more creative is a myth,” he explains. “But the experience of being marginalized as a gay person helps you create certain forms of expression — whether it be painting, or poetry, or plays or literature, or music. That expression coming from a minoritized position resists mainstream normativity and is then exciting.”

This is part of the reason why gayborhoods began attracting so many artists, poets, musicians, and other creators of countercultural work — regardless of their sexuality.

Bronski also claims that this is an urban phenomenon. While LGBT+ people also lived in suburbs and rural areas nationwide, these areas are much more likely to encourage privacy. In places where people own their homes and live behind picket fences, it’s less likely that they’ll interact in the streets with other likeminded people. So, gayborhoods have tended to form in urban centers.

“One of the prerequisites is that you have to be able to be public,” Bronski says. “Neighborhoods are really incubators or crucibles of culture — whether it be theater, art galleries or studios, people making music on the street, or people doing graffiti on the street.”

The Straightening of Gayborhoods

Over time, a confluence of economic and social factors have led to gentrification and to LGBT+ people moving out of historic gayborhoods like Greenwich Village, the Castro, and the South End. Notably, the AIDS crisis of the ‘80s that disproportionately affected the LGBT+ population led to tragic deaths of thousands of people who had once lived in these spaces. Additionally, a growing acceptance of LGBT+ people in recent years has also afforded them greater freedom in choosing where to live.

But while some of these gayborhoods have seemingly “disappeared,” others have popped up in their place.

Once again, this comes back to the changing needs of real estate.

Bronski recalls a once-thriving gay bar in the Fenway area of Boston called The Eagle, which no longer exists: “If you go down there now, the neighborhood is completely all high rises — and that has nothing to do with kicking gay people out. That has to do with real estate development — often to the detriment of poor people that are gay or straight that are living there.”

In an interview with Vox about his book There Goes The Gayborhood?, sociologist Amin Ghaziani describes a shift happening from historic gayborhoods to new communities.

“In Chicago, for instance, the existing Boystown neighborhood [now called Northalsted] may be straightening, but there's a new emergence of same-sex partner households in Andersonville,” he says. “There are also many gay men and lesbians who are moving to even the next neighborhood north, Rogers Park. I know there's a similar movement that's happening in Washington, DC, San Francisco, and San Diego. Perhaps we live in an age of plurality and multiplication rather than disappearance.”

The prevalence of social media has also had a profound effect on how people within the LGBT+ community are able to meet and congregate. Now, rather than meeting in the nearest bar or café, they meet, date, organize, and socialize online.

Monuments of History

Like all neighborhoods, gayborhoods adapt, change, disappear, and reappear again. But their cultural, social, and political legacies are impermeable.

Chicago's Northalsted neighborhood. Photo credit: Joe Hendrickson

Chicago's Northalsted neighborhood. Photo credit: Joe Hendrickson

The physical markers of this history — the rainbow crosswalks and flags, gay pride parades and other events — have turned gayborhoods into monuments and tourist destinations.

This is one measure that Ghaziani recommends in his book as a response to the “straightening” trend of historic neighborhoods: “Chicago became the first city in the world to use tax-funded dollars to municipally mark its gayborhood — Boystown [now called Northalsted]. They installed art deco–styled, rainbow-colored pylons along North Halsted Street, which is a main clear artery of the commercial and night life district in the city. We've seen versions of this in many cities across North America… These kinds of commemorative markers do not require us to deny the realities of residential change. All neighborhoods change. Gay neighborhoods are not an exception to this most basic insight of city life. These markers embrace that reality while still honoring the heritage and history of these particular neighborhoods.”

So, the next time you’re visiting a new city with a gayborhood, consider taking a stroll down one of these rainbow-colored main streets and reflecting on the decades of activism it took to create it.

Top cities

Atlanta Apartments

1,825 apartments starting at $630/month

Austin Apartments

6,133 apartments starting at $600/month

Baltimore Apartments

1,423 apartments starting at $640/month

Boston Apartments

5,609 apartments starting at $425/month

Charlotte Apartments

2,980 apartments starting at $570/month

Chicago Apartments

5,458 apartments starting at $400/month

Dallas Apartments

5,455 apartments starting at $625/month

Fort Worth Apartments

2,695 apartments starting at $695/month

Houston Apartments

5,813 apartments starting at $450/month

Las Vegas Apartments

1,016 apartments starting at $795/month

Los Angeles Apartments

12,712 apartments starting at $750/month

Miami Apartments

702 apartments starting at $1,200/month

Milwaukee Apartments

1,106 apartments starting at $475/month

New York Apartments

8,874 apartments starting at $600/month

Oakland Apartments

983 apartments starting at $850/month

Orlando Apartments

877 apartments starting at $895/month

Philadelphia Apartments

3,614 apartments starting at $500/month

Phoenix Apartments

3,461 apartments starting at $592/month

Pittsburgh Apartments

1,382 apartments starting at $590/month

Portland Apartments

2,260 apartments starting at $575/month

Raleigh Apartments

1,471 apartments starting at $550/month

San Antonio Apartments

3,372 apartments starting at $525/month

San Diego Apartments

2,860 apartments starting at $650/month

San Francisco Apartments

664 apartments starting at $500/month

San Jose Apartments

516 apartments starting at $1,000/month

Seattle Apartments

3,520 apartments starting at $452/month

Tampa Apartments

776 apartments starting at $808/month

Washington DC Apartments

2,256 apartments starting at $910/month